This post outlines what makes a good machine leaning portfolio, with useful examples to help you begin to understand the type of project that gets noticed by big companies.

By Edouard Harris, Founder @SharpestMindsAI (YC W18).

I’m a physicist who works at a YC startup. Our job is to help new grads get hired into their first machine learning jobs.

Some time ago, I wrote about the things you should do to get hired into your first machine learning job. I said in that post that one thing you should do is build a portfolio of your personal machine learning projects. But I left out the part about how to actually to do that, so in this post, I’ll tell you how. [1]

Because of what our startup does, I’ve seen hundreds of examples of personal projects that ranged from very good to very bad. Let me tell you about two of the very good ones.

The all-in

What follows is a true story, except that I’ve changed names for privacy.

Company X uses AI to alert grocery stores when it’s time for them to order new inventory. We had one student, Ron, who really wanted to work at Company X. Ron wanted to work at Company X so badly, in fact, that he built a personal project that was 100% dedicated to getting him an interview there.

We don’t usually recommend going all-in on one company like this. It’s risky to do if you’re starting out. But — like I said — Ron really wanted to work at Company X.

So what did Ron build?

The red bounding boxes indicate missing items.

- Ron started by duct taping his phone to a grocery cart. Then he drove his cart up and down the aisles of a grocery store while he recorded the aisles with his camera. He did this 10–12 times at different grocery stores.

- Once he got home, Ron started to build a machine learning model. His model identified empty spots in grocery store shelves — places where the cornflakes (or whatever) were missing from the shelves.

- Here’s the awesome part: Ron built his model in real time, on GitHub, in full public view. Every day, he’d push improvements to his repo (improved accuracy, and chronicle the changes in his repo’s README.

- When Company X realized Ron was doing this, Company X was intrigued. More than intrigued. In fact, Company X was slightly nervous. Why would they be nervous? Because Ron had unknowingly, and in a few days, reproduced a part of their proprietary tech stack. [2]

Company X is exceptionally competent, and their technology is among the best in their industry. Nonetheless, within 4 days, Ron’s project had grabbed the direct personal attention of Company X’s CEO.

The pilot project

Here’s another true story.

Alex is a history major with a minor in Russian studies (really). Unusually for a history major, he got interested in machine learning. Even more unusually, he decided he would learn it, despite having never written a line of Python.

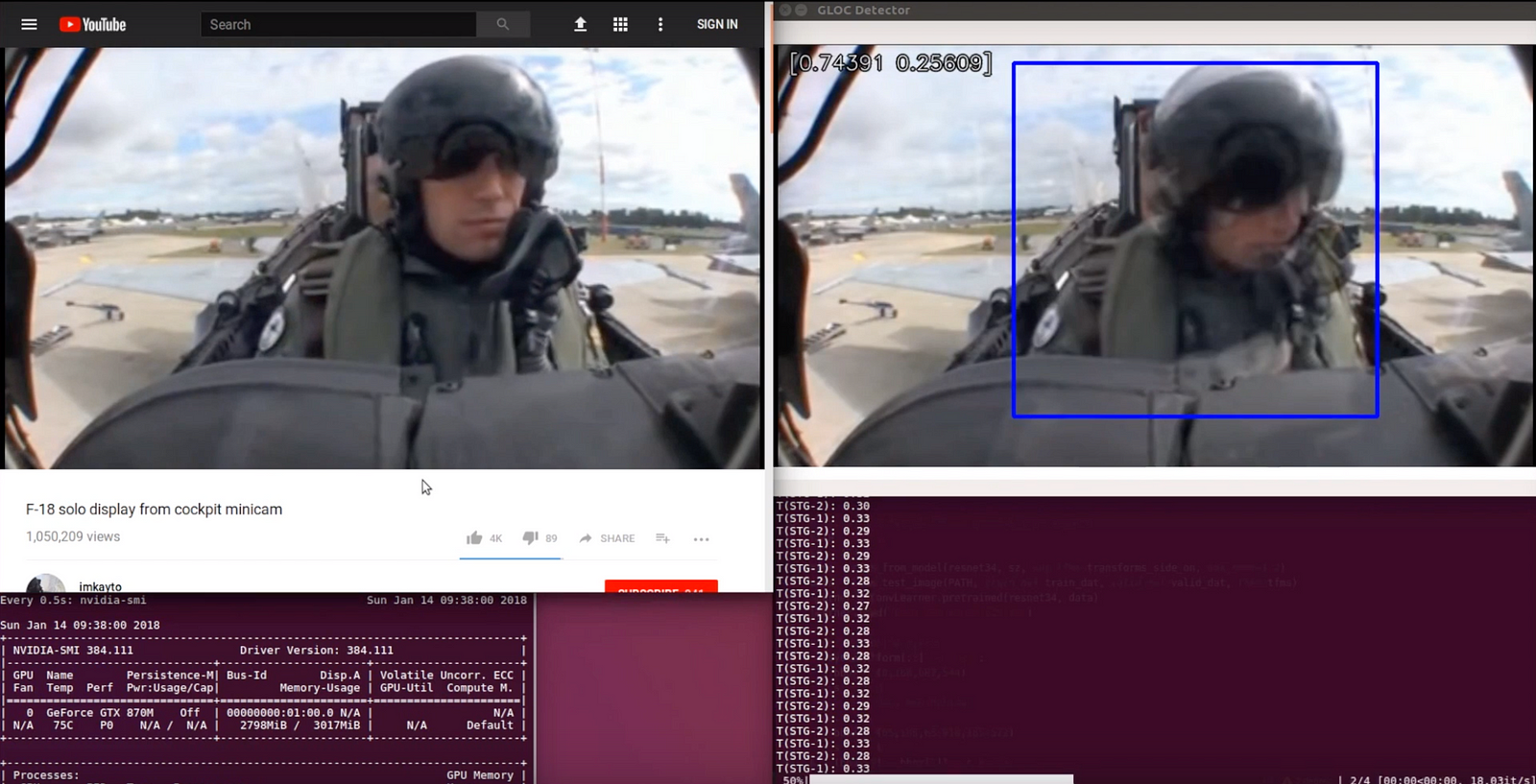

Alex chose to learn by building. He settled on building a classifier to detect if fighter pilots were losing consciousness in their airplanes. Alex wanted to detect this by looking at videos of pilots. He knew it was easy for a person to tell, just by looking, when a pilot is unconscious, so Alex figured it should be possible for a machine to tell, too.

Here’s what Alex did, over the course of several months:

A demo of Alex’s G-force induced loss-of-consciousness detector.

- Alex went on YouTube and downloaded every video clip of pilots flying planes, taken from the cockpit. (In case you’re wondering, there are a few dozen of these clips.)

- Next he started to label his data. Alex built a UI that let him scroll through thousands of video frames, press one button for “conscious” and another button for “unconscious”, and automatically save that frame in the correctly labeled folder. This labeling was very, very boring and took him many, many days.

- Alex built a data pipeline for the images that would crop the pilot out of the cockpit background — to make it easier for his classifier to focus on the pilot. Finally, he built his loss-of-consciousness classifier.

- At the same time as he was doing all these things, Alex was showing snapshots his project to hiring managers at networking events. Every time he took out his project and showed it off (on his phone), they asked him how he did it, about the pipeline he built, and how he collected his data. But they never quite got around to asking about his model’s accuracy — which was under 50%.

Alex planned to improve his accuracy, of course, but he was hired before he got the chance. It turned out that the visual impact of his project, and his relentless resourcefulness in data gathering, mattered much more to companies than how good his model actually was.

Did I mention Alex is a history major with a minor in Russian studies?

What they have in common

What made Ron and Alex so successful? Here are four big things they did right:

- Ron and Alex didn’t spend much effort on modelling.I know this sounds strange, but for many use cases nowadays modelling is a solved problem. In a real job, unless you’re doing state of the art AI research, you’ll be spending 80–90% of your time cleaning your data anyway. Why would your personal project be different?

- Ron and Alex gathered their own data.Because of this, they ended up with data that was messier than what you’d find in on Kaggle or the UCI data repository. But working with messy data taught them to deal with messy data. It also forced them to understand their data better than if they’d downloaded it from an academic server.

- Ron and Alex built visual things.An interview isn’t about your skills being objectively assessed by an all-knowing judge. An interview is about selling yourself to another human being. Human beings are visual creatures. So if you pull out your phone and show the interviewer what you built, it’s worth making sure that what you’ve built looks interesting.

- What Ron and Alex did seems insane.And it was insane. Normal people don’t duct tape their phones to shopping carts. Normal people don’t spend their days cropping pilots out of YouTube videos. You know who does that? People who will do whatever it takes get their work done. And companies really, really want to hire those people.

What Ron and Alex did might might seem like too much work, but really, it isn’t much more than you’d be expected to do in a real job. And that’s the whole point: when you don’t have work experience doing X, hiring managers will look for things you’ve done that simulate work experience doing X.

Fortunately you only need to do build a project at this level once or twice — Ron and Alex’s projects got reused over and over for all their interviews.

So if I had to summarize the secret to a great ML project in one sentence, it would be: Build a project with an interesting dataset that took obvious effort to collect, and make it as visually impactful as possible.

And if you have a project idea and you aren’t sure if it’s good — ask me on Twitter! My handle is @neutronsNeurons, and my DMs are open 🙂

***************************************************************

[1] In case you’re wondering why this is important, it’s because hiring managers try to assess you by looking at your track record. If you don’t have a track record, personal projects are the closest substitute.

[2] Of course Ron’s attempt was far from perfect: Company X had devoted orders of magnitude more resources to the problem than he had. But it was similar enough that they quickly asked Ron to make his repo private.

Bio: Edouard Harrisis the founder of @SharpestMindsAI (YC W18), physicist and machine learning engineer.

Source: The Cold Start Problem: How to Build Your Machine Learning Portfolio