Putting the Power of Kafka into the Hands of Data Scientists

Over a year ago, my fellow data infrastructure engineers and I broke ground on a total rewrite of our event delivery infrastructure. Our mission was to build a robust, centralized data integration platform tailored to the needs of our Data Scientists. The platform would be fully self-service, so as to maximize the Data Scientists’ autonomy and give them complete control over their event data. Ultimately, we delivered a platform that is revolutionizing the way Data Scientists interact with Stitch Fix’s data.

In two parts, this post peeks into Stitch Fix’s Data Science culture and delves into how it drove the fundamental decisions we made in our lowest levels of data infrastructure. Part 1 discusses our design process, explains our guiding philosophy around self-service tooling and explores our data integration platform concept. Part 2 is a technical dive into the decisions we made and a walk-through of the whole architecture.

Part 1: The Design

Around the time we started working on our event delivery rewrite, much of the data in our Data Warehouse was being collected from database snapshots. This is a style of data pipeline that has been ubiquitous across the industry for decades, as database snapshots are useful for plenty of things, and are generally easy to set up and maintain. They have a few drawbacks, however:

- You don’t know how the database’s state changes in between snapshots.

- Data can only be analyzed once a snapshot is taken—analysis cannot happen in real time.

- Only data that exists in the OLTP database can be analyzed, e.g. state that is necessary for operational applications. Context and metadata about the state is often missing.

Events can solve these problems. Building a robust, centralized and scalable system dedicated to collecting event data would greatly augment the database snapshot data and unlock loads of potential for the Data Scientists.

Self-Service Event Delivery

Our main requirement for this new project was to build infrastructure that would be 100% self-service for our Data Scientists. In other words, my teammates and I would never be directly involved in the discovery, creation, configuration and management of the event data. Self-service would fix the primary shortcoming of our legacy event delivery system: manual administration that was performed by my team whenever a new dataset was born. This manual process hindered the productivity and access to event data for our Data Scientists. Meanwhile, fulfilling the requests of the Data Scientists hindered our own ability to improve the infrastructure. This scenario is exactly what the Data Platform Team strives to avoid. Building self-service tooling is the number one tenet of the Data Platform Team at Stitch Fix, so whatever we built to replace the old event infrastructure needed to be self-service for our Data Scientists. You can learn more about our philosophy in Jeff Magnusson’s post Engineers Shouldn’t Write ETL.

Making the event delivery infrastructure completely self-service to Data Scientists was a unique and interesting challenge. Having spent years working on real-time, streaming infrastructure prior to Stitch Fix, I knew how to craft efficient Kafka applications, how to monitor them, how to scale them, and I knew how to maintain a production Kafka cluster. But how could we, a lean team of three, not only deploy our own brand-new Kafka cluster, but also design and build a self-service event delivery platform on top of it? How could we give Data Scientists total control and freedom over Stitch Fix’s event data without requiring them to understand the intricacies of streaming data pipelines?

Designing the Data Integration Platform

Designing our self-service layer on top of Kafka began with an extensive period of research. Noteworthy inspirations for our data integration platform concept came from Martin Kleppmann’s Designing Data-Intensive Applications: The Big Ideas Behind Reliable, Scalable, and Maintainable Systems and Kafka Co-Creator Jay Kreps’ article The Log: What Every Software Engineer Should Know About Real-Time Data’s Unifying Abstraction.

In the article, Kreps talks about the power of a centralized log pipeline and at one point focuses specifically on the simplification of data integration, where he provides this definition:

Data integration is making all the data an organization has available in all its services and systems.

He goes on to say this, which I found particularly compelling:

You don’t hear much about data integration in all the breathless interest and hype around the idea of big data, but nonetheless, I believe this mundane problem of “making the data available” is one of the more valuable things an organization can focus on.

I was enamoured by this idea of “making all the data an organization has available in all its services and systems.” What could be more powerful than giving the Data Scientists easy, self-service access to all the data across the whole company?

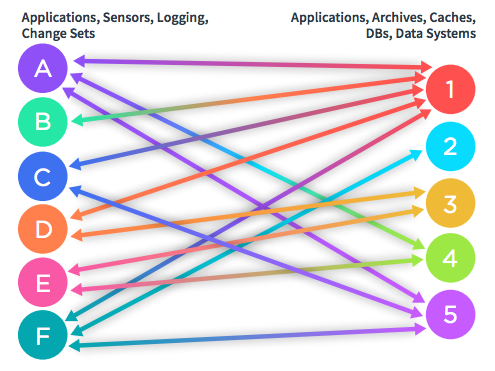

To explain how this would all work, I’ll paraphrase Kreps’ idea of data integration and how it solves the problem of making data available everywhere. First, picture all the services, applications, specialized data systems and databases within a company. As the company evolves, use cases pop up that involve connecting one thing to another in order to pass data back and forth. It is likely that the teams building these connections build a one-off dedicated solution, because it is quicker and easier in the short term than building a general purpose solution. When enough teams do this, an architecture such as the one shown in Figure 1 materializes.

Figure 1. Data Integration without a Centralized Log Pipeline

Figure 1. Data Integration without a Centralized Log PipelineEach arrow is a custom connection that has to be individually developed and maintained. To achieve total connectivity in which every process can stream data back and forth between every other process within the company, you’d have to build n2connectors, where n is the total number of processes within the company. Any engineer will tell you this is preposterously unscalable.

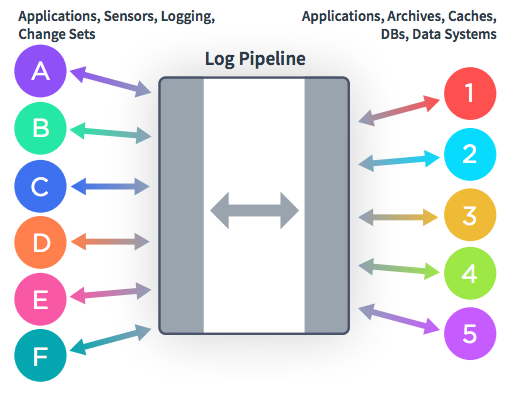

Now imagine the same set of services, applications, specialized data systems and databases with the addition of a centralized log pipeline. Instead of passing data directly between processes, the data flows through the centralized pipeline, yielding an architecture as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Data Integration with a Centralized Log Pipeline

Figure 2. Data Integration with a Centralized Log PipelineThis approach reduces connections by an order of magnitude and accomplishes the same goal—data can flow from any process to any other process within the company. The beauty of this architecture is that every connector is quite uniform in function, which allows for a general purpose platform that handles getting data in and out of the central pipeline. This platform centralizes and simplifies the mechanisms by which data is transported from A to B, making everyone’s job much easier.

This general purpose platform would be our data integration platform. Each connector would be code written, deployed and maintained by my teammates, and we would build a simple web UI for Data Scientists to configure their connectors and easily get data in and out of the central log pipeline. Inspired by the network of roads and highways that connect everything in the world, we decided to call the platform The Data Highway.

Part 2: Building

With a clear concept of what we would build, we entered another phase of research, this time focused on comparing specific technologies. Because the data infrastructure world is still blossoming into a mature ecosystem, there were many young technologies to choose from. I’ll outline the reasons we chose the solutions we did.

Choosing a Message Broker

Currently, the most frequently adopted solutions for high-volume, distributed message brokers are Apache Kafka, Amazon Kinesis and Cloud Pub/Sub. We ruled out Cloud Pub/Sub early on simply because integrating our Amazon Web Services (AWS) stack with a Google Cloud Platform (GCP) product would be too costly. That left Kinesis and Kafka.

I could devote an entire post to this decision alone because there were a multitude of factors we considered, many of which were nuanced and difficult to objectively measure. Our data volume is modest enough that either Kafka or Kinesis would have worked from a purely performance perspective. Hence, our decision-making focused on questions like which technology will be easier to write tooling for? Which technology will give us a better foundation to build and maintain our platform on top of? Which technology will be the easiest to maintain and evolve? Answering these questions would have been very difficult were it not for the team’s collective experience using both technologies.

A year prior to starting this project, we had stood up a basic event delivery system using Kinesis and AWS Lambda. The system was running decently well–especially considering how easy it was to spin up–but we were quickly outgrowing it for a number of reasons:

- A lot of manual setup was required for new datasets.

- Maintaining separate staging and production environments was tricky due to the way that the Lambda functions were set up.

- We had to make some architectural trade-offs to work around Kinesis’ throttling policies.

- Worst of all, the system had grown too complex to be self-service for Data Scientists

Ultimately, we had to decide whether to re-architect our existing Kinesis system or start from scratch with a Kafka-based system.

After some debate, we chose Kafka. Although the ease of a hosted solution like Kinesis was very tempting, the scales tipped towards Kafka because:

- We wanted something that would integrate well with AWS and non-AWS products alike.

- We wanted fine-grained control over our deployment.

- An in-house deployment of Kafka would scale more than Kinesis and would be cheaper in the long run.

- We wanted to improve our involvement in the open-source community.

- The Kafka ecosystem is richer and more fully featured than the Kinesis ecosystem.

- As far as databases goes, Kafka has a relatively low operational burden.

Comparing Data Integration Solutions

For the data integration layer on top of Kafka, we considered many options. There is a budding ecosystem for these kinds of tools in the open-source world, so we wanted to use an existing technology rather than write our own system. The primary contenders were Apache Beam, Storm, Logstash and Kafka Connect.

Apache Beam is a Swiss Army knife for building batch and streaming ETL pipelines. Its Pipeline I/O feature comes with a suite of built-in read and write transforms. These transforms read and write data from a variety of places, and there is ongoing work to add many more options for consuming and producing data. Apache Beam was not designed to be a data integration solution, however, although it has some data integration capabilities. It is a flexible data processing SDK, not a specialized system for getting data from A to B. We would have had to write a ton of code to support fully self-service data pipelines that are configurable with a click of a button.

Apache Storm was a potential option, but it would have been costly to build the self-service interface on top of it, since the data flow pipelines have to be written as code and deployed yourself. Apache Storm is better suited to use cases where you have a very specialized streaming pipeline with clearly defined requirements. We needed something that was multipurpose and would be easily configurable even in a runtime environment.

Logstash is handy because it has so many integrations—more than any other option we researched. It’s also lightweight and easy to deploy. Yet Logstash lacked important resiliency features, such as support for distributed clusters of workers and disk-based buffering of events. As of version 6.0 both of these features are now implemented, so Logstash could work for a data integration layer. But its biggest drawback for our use case is that the data flows are configured using static files written in Logstash’s (somewhat finicky) DSL. This would make it challenging to build the self-service interface. (Note: We did actually end up using Logstash to ingest Syslog data—more on that later.)

Finally, we investigated Kafka Connect. Kafka Connect’s goal is to make the integration of systems as simple and resilient as possible. It is built on top of the standard Kafka consumer and producer, so it has auto load balancing, it’s simple to adjust processing capacity and it has strong delivery guarantees. It can run in a distributed cluster, so failovers are seamless, as well as scaling and rolling restarts. It is stateless since it stores all its state in Kafka itself. There is a growing array of open-source connectors that can be downloaded and installed into your deployment. If you have special requirements, the API for writing your own connectors is simple and expressive, making it straightforward to write custom integrations. The most compelling feature for us was Kafka Connect’s REST interface for creating, deleting, modifying or pausing connectors in a runtime environment. This provided a super-easy way to build our self-service interface.

It’s not surprising that Kafka Connect was the best solution for our needs. The inspiration for our data integration platform came primarily from the creators of Kafka. They designed Kafka Connect specifically to help bring their vision to life and to solve the oft underestimated challenge of simplifying data integration. I can confirm that Kafka Connect delivers. It is a supremely well-engineered piece of technology that is the workhorse of our whole platform. It saved us a tremendous amount of effort, and it is getting better every day as more integrations are being added and its features mature. It is well-maintained and we were able to get a few patches merged upstream without much ado. It’s not totally perfect–it has some painful jar hell problems–but overall we’re very happy with it.

Putting All the Pieces Together

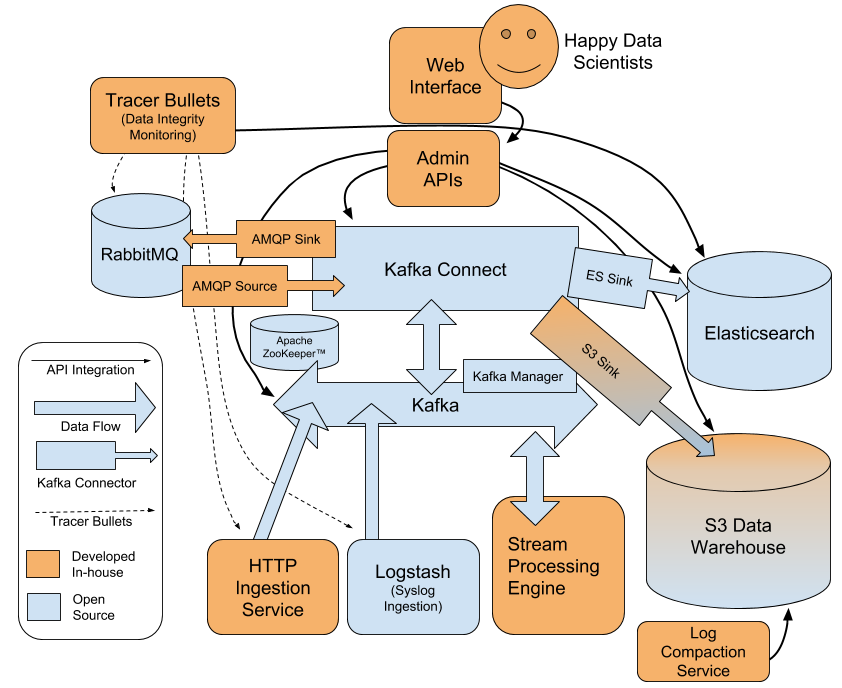

Now for the moment you’ve all been waiting for… the architecture diagram!

Figure 3. Data Highway Complete Architecture Diagram

Figure 3. Data Highway Complete Architecture DiagramFor the most part, we were able to leverage open-source technologies to power our platform. There were a handful of things we wrote ourselves to fill in the gaps, which I’ll briefly cover.

Ingesting HTTP and Syslog Data

After standing up Kafka and Kafka Connect, we wrote a service to ingest HTTP data, and we deployed Logstash to handle ingesting Syslog data. In the early days of development, we wrote an HTTP Connector that was deployed in the Kafka Connect infrastructure, but we scrapped it because we decided Kafka Connect should only handle transporting data that is already at rest either within Kafka or in an external system. Events that are being emitted and are not yet at rest (e.g., most of the data coming in via HTTP and Syslog) should go straight to Kafka. This gives us the flexibility to shut down our Kafka Connect infrastructure in times of emergency or maintenance, without risking the loss of data. This has come in handy a few times, and generally simplifies the Kafka Connect deployment.

User Interface

Before building our slick web UI, we built a backend service to tie together all the various in-house and open-source components of the whole platform. This administrative service wrapped the Kafka Connect REST API and exposed a much simpler API that performed validation and filled in default parameters. It can also do various other things such as list Kafka topics, sample Kafka topics and create tables in the Hive Metastore when new topics are written to the data warehouse. The web UI is a React application built on top of this unified admin API. The web UI has wizards to help Data Scientists set up their data pipelines and walk them through the process.

A very common example user flow would be something like this: a Data Scientist sends their log data via HTTP to a new Kafka topic, navigates to the web UI, follows the wizard to set up an S3 sink that pumps their logs into a table in the Data Warehouse, and voila, their data flows into a new hive table in the data warehouse in real time.

Data Transformation

Data often exists in a format that’s not quite what you need. For trivial use cases we were able to leverage Kafka Connect’s transforms functionality to munge the data. For non-trivial transformations, particularly when we want to join the streaming data on data at rest in the data warehouse, we built a lightweight, self-service stream-processing engine in Python. Kafka streams would have been nice to use for this, as it is more powerful than our version, but Kafka streams does not currently support Python. Since Python is the crowd favorite among the Data Scientists, we wanted to provide a Python interface for them so that it could be self-service.

The stream-processing engine provides a runtime environment with automated monitoring and log collection. The Data Scientists can write an arbitrary Python function that runs on each event, and they deploy it using tools we provide. A lot of the deployment infrastructure necessary to build this stream-processing engine existed already (we have a very similar tool for standing up HTTP endpoints), so it was straightforward to build.

Data Model

All the data that flows through the platform is JSON formatted, and conforms to a data model that we enforce at all the ingestion points. The data model is an envelope-style format that looks like this:

{

“metadata”: {

“id”: “<unique id>”

“timestamp”: “<creation timestamp>”

“version”: “<user defined version>”

},

“payload”: {

... arbitrary json blob ...

},

“event_name”: “<usually topic name, but not always>”

}

This style of data formatting was a holdover from the legacy event system and is not necessarily my ideal solution. To make the migration as seamless as possible, we decided to keep the JSON, envelope-style data model and enhance it with the addition of the metadata blob. Having such a simple way to encode data has actually been pretty convenient, although it is inefficient in terms of disk, memory and CPU usage, and we’re limited in our ability to guarantee events will have the fields Data Scientists expect them to have. It also doesn’t play nicely with Kafka’s ecosystem, which generally expects topics to have schemas. This has been a headache in some situations, particularly when installing new Kafka Connect connectors. Schemas, a schema registry and data lineage are things we are planning to explore. If you are building a system like this from scratch, I would heartily recommend you start with schemas right off the bat so you never have to later migrate to schemas.

Log Compaction

When data is flushed to the data warehouse, it is written in small batches of files. These small and numerous files clog up query systems such as Spark and Presto, so we wrote a log compaction service that asynchronously compacts the small files into larger ones. (This was actually part of our legacy event infrastructure and we were able to continue using it.) This lets us write data to the data warehouse that can be queried in real-time without cluttering the data warehouse with tiny files. Eventually we may look into Uber’s Hudi project to handle this logic.

Monitoring

A crucial part of any system is the ability to know if it’s working or not. For this, we built a system of “tracer bullets” whereby we send special tracer events into every possible ingestion point and route the data to every possible destination. When we send a tracer bullet, we persist a piece of metadata about it, including its unique ID, sent timestamp, ingestion point and the list of destinations where the tracer bullet should eventually arrive. We continuously query the metadata and the destination systems awaiting the arrival of the tracer bullets, measuring the total latency when they do arrive, and alerting on any lost or duplicate tracer bullets. This method of ensuring the integrity of the system is nice because it uses exactly the same interfaces that the users experience and it is easily extensible. It does not depend on emitting metrics upon every write and read into the system; the caveat, however, is that you cannot guarantee the integrity of the entire system all of the time, since it is more like sampling the flow of data rather than measuring all the data. For our use case this trade-off was okay; however, we are investigating ways to make our monitoring more complete.

Conclusion

Never have I worked on a project this challenging that involved writing so little code. We spent about two-thirds of the project timeline on research, design, debate and prototyping. Over months we whittled away at every component until it was as small and maintainable as possible. We tried to salvage as much as we could from our legacy infrastructure. More than once we submitted patches upstream to Kafka Connect to avoid extra complexity on our end. We still strive to keep our Kafka infrastructure as current as possible so that we can continue to submit patches whenever necessary.

The Data Highway has been running in production for almost eight months now, and we have yet to experience a major outage (knock on wood). The department has created several hundred topics with hundreds of connectors running in our distributed Kafka Connect deployment. The infrastructure hums along smoothly with very little operational burden or manual administration, freeing up our time to work on other impactful projects, while giving Data Scientists autonomy and freedom.

I recall a moment early on in the project when I overheard a conversation between a Data Scientist and engineer on one of the product teams. They were discussing ways that they could reliably pass data back and forth between their systems, but their conversation fizzled out in frustration because at that time there was no good way to do so. Considering the hundreds of topics and connectors that our Data Scientists created in the past year, there must have been dozens of similarly frustrating conversations taking place all across the department. Now our Data Scientists have the freedom and autonomy to own their event-driven destinies, and it’s tremendously gratifying to know that those conversations are no longer ending in frustration, but rather fulfillment.

Source: Putting the Power of Kafka into the Hands of Data Scientists